The Daoist Paradigm of ‚The Soft overcomes the Hard‘ – Emphasizing the Feminine in Leadership

Recent newspaper articles keep reminding us that women in developed countries are still exposed to discrimination and gender inequality at the workplace in a number of professional fields. Yet, global consultancies like McKinsey stress in articles like Women Matter: Time to accelerate the business case for gender diversity, and more specifically gender parity. Hence gender diversity through increased gender parity should be a strategic business imperative. At the same time, a number of academic publications also underline the business case for more gender equality, for example by highlighting women’s leadership style being better aligned with what is perceived as good leadership today. Yet, the broader question framing this article is what kind of leadership and management we actually need with regard to work in the 21st century. And, more importantly, what kind of values should be guiding our leadership approach accordingly. This article proposes an alternative way of leadership based on values and principles derived from Chinese philosophy, in specific Daoism. These Daoist values and behavioural principles emphasise the feminine, yin 阴, over the masculine, yang 阳, which could open up a new way for a more inclusive leadership approach.

Why We Turned Towards the East to Learn More About Leadership

What was driving us in writing an article that is dealing with a more Eastern philosophical perspective on leadership? First, the discipline of philosophy generally provides us with a number of interesting, critical insights when it comes to values and related discussions in general. Second, Eastern philosophy offers us different values to compare, discuss and to learn from. After all, social values are a product of a country’s history and culture. In the age of globalisation there is a huge opportunity to learn from other cultures. Daoism in that regard is a very inspiring philosophy. Its dialectical concepts seem to be unparalleled in Western philosophy. This is why we chose the paradox of the soft overcoming the hard to illustrate this way of thinking and to argue for new perspectives.

This article proposes an alternative way of leadership based on values and principles derived from Chinese philosophy, in specific Daoism. These Daoist values and behavioural principles emphasise the feminine, yin 阴, over the masculine, yang 阳, which could open up a new way for a more inclusive leadership approach. The theoretical contribution of this article is two-fold. It adds to the broader field of feminist organisational theory and to the discussion of how to sustain the organisation in the future, as Daoist values and principles could present a more balanced approach to organisation and leadership more generally.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: First, we will look into barriers to leadership faced by women, second, different leadership styles and third, the question of ‘ideal’ leadership. In the fourth part, we will look into Chinese philosophy and Daoism including the concept of yin-yang. This provides the foundation for the introduction of a new leadership approach derived from Daoist values in the fifth and last part. This article closes with a conclusion and concrete insights formulated as key take-aways.

Why We (Still) Need to Discuss Female Leadership

Recent newspaper articles for example in The New York Times and The Guardian keep reminding us that women in developed countries are exposed to discrimination and gender inequality at the workplace until today in a number of professional fields like science, technology, literature, or surgery amongst others. Yet, global consultancies stress gender diversity, and more specifically gender parity, as these could positively affect financial performance, innovation revenue and even value creation. Accordingly, gender diversity through increased gender parity should be a strategic business imperative. Moreover, increasing gender diversity and gender parity are also imperative for a functioning and further growing economy.

However, in a study by Bain & Company only 55 per cent of male employees vs. 76 per cent of female employees believed in the business case for gender parity. Here, the so called double bind – conflicting expectations about women’s characteristics and abilities in the workplace on the one hand, such as being caring, non-confrontational, non-assertive etc. and leadership requirements including assertiveness, aggressiveness, directness on the other hand – is standing in the way of having more women in higher management, as often they are not perceived as being equally qualified for leadership. In addition, due to a double standard applied to women’s performance they are required to demonstrate extra confidence and ability compared to men in order to receive the same recognition. This phenomenon of women being stuck in the – often male-dominated – corporate hierarchy and not being able to reach leadership positions is called glass ceiling, which indicates a plateau for women at levels below top management.

More recent studies by McKinsey on women in the workplace declare a slow progress globally regarding gender parity especially at higher management levels across developed countries, with the US apparently stalling. At the same time, a number of academic publications underline the business case for more gender equality, for example by highlighting women’s leadership style being better aligned with what is perceived as good leadership today; reducing turnover rates of women and thereby organisational brain drain; improving organisational effectiveness by expanding the talent pool; being perceived as a fair employer, as well as the link between gender diversity, for example on board and C-suite level, and financial performance.

Yet, aside the question of how to enable more women to become leaders, the broader question framing this article is what kind of leadership and management we actually need with regard to work in the 21st century. And, what kind of values should be guiding our leadership approach accordingly.

The Multiple Barriers to Leadership Women Continue to Face Today

The two American leadership researchers Amy B. Diehl and Leanne Dzubinski conducted a more comprehensive macro, meso and micro-level analysis of leadership barriers affecting women based on qualitative research called Making the Invisible Visible: A Cross-Sector Analysis of Gender-Based Leadership Barriers. In total, they identified 27 barriers distributed across the societal (macro), organisational (meso) and individual (micro) level. On the societal level, six barriers were identified which range from women’s voices being controlled, their choices being culturally constrained, over gender stereotypes and gender unconsciousness to specific leadership perceptions, and generally higher levels of scrutiny perceived compared to men.

On the individual level, another five barriers emerged such as constraints regarding communication style, conscious unconsciousness of gender (bias), assuming personal responsibility for organisational problems, a self-imposed psychological glass ceiling, and conflicts in balancing private and professional life (ibid.).

On the organisational level, however, most of these barriers (16 of 27) are to be found. These include a general devaluation of women’s more communal leadership style and lack of full recognition of their abilities due to a masculine organisational culture and norms; systemic lacks within the organisation regarding mentoring, sponsorship and support, i.e. development, of women; the glass cliff phenomenon (selecting women predominantly for high-risk leadership roles with the likelihood to fail); procedural insufficiencies expressed in unequal remuneration and unequal performance standards; exclusion practices such as no access to informal networks and male gatekeeping and worse, discrimination and even workplace harassment. Two more barriers according to Diehl and Dzubinski inhibiting the advancement of women in organisations are the ‘Queen Bee Effect’ and tokenism.

The comprehensive observation and analysis by Diehl and Dzubinski essentially capture previous discussions regarding barriers to leadership faced by women but now systematically linked to the macro, meso and micro level. This brings to the fore the full scope of barriers in an organisational context and additional reinforcing mechanisms from both macro and micro level.

Differences in Leadership Styles

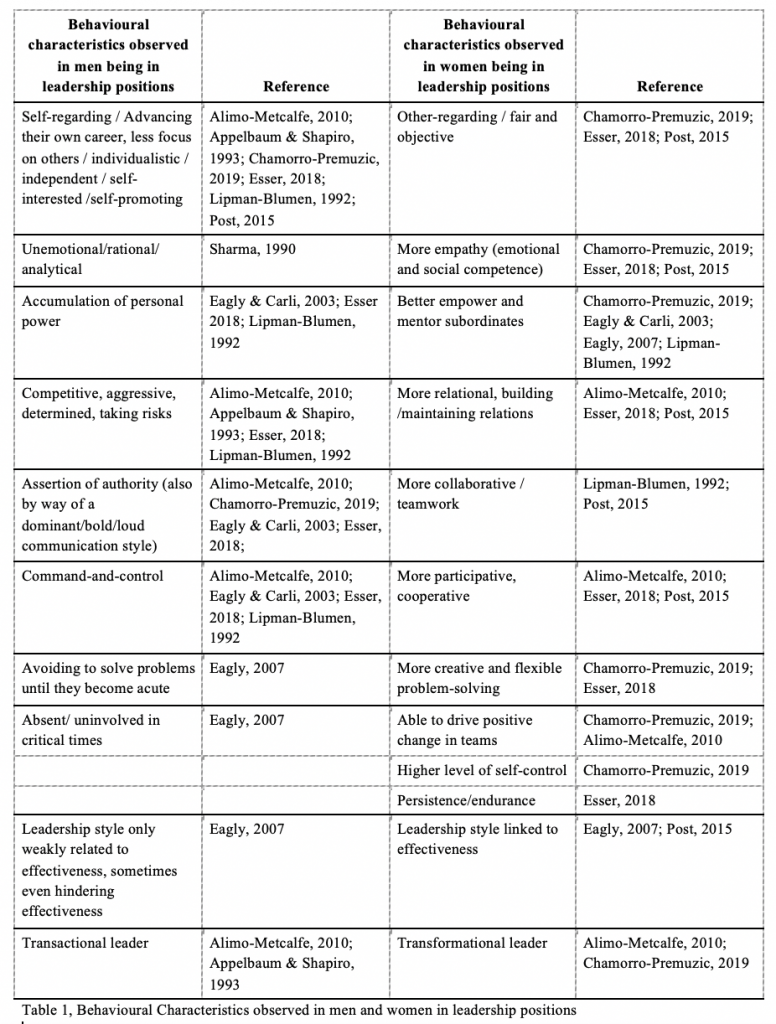

In light of the barriers mentioned, the question is what actually characterises the female way of leadership for which women are apparently not adequately recognised and appreciated. These are outlined in Table 1 and contrasted with characteristics of a rather typical male way of leadership.

Yet, we need to bear in mind that the discussion of gender and leadership is more complex. The information outlined in the table is based on publications drawing on empirical studies. These are reflections of characteristics observed in men and women respectively, whereas men and women linguistically speaking are nouns representing biological categories. However, next to our biological sex, which is predominantly perceived in dichotomous categories of either man/male or woman/female, there is also gender. Gender according to the gender scientist Judith Butler in her famous work Undoing Gender “is a kind of a doing, an incessant activity performed”, expressed in what we call masculine or feminine. The latter two are not necessarily tied and in line with the corresponding biological sex but describe the cultural part of what it is to be a man or a woman, and hence are describing culturally variable characteristics.

This is further supported by Butler, claiming that attribution of feminine to females or women happens on a normative basis. Accordingly, being a woman does not necessarily entail feminine behaviour or character traits. Similarly, designations like masculine and masculinity only capture those ways of behaviour and character traits found in dominant male groups, which are also referred to as hegemonic in contrast to other, subordinated masculinities. Hence, these labels of feminine and masculine only capture the socio-cultural characteristics of the most dominant group within the respective biological sexes. Yet, with regard to empirical studies it is difficult to determine with certainty to what extent the behavioural characteristics observed need to be attributed to biological sex or predominantly to gender, i.e. the question whether these characteristics are female or feminine.

That women do not necessarily behave in gender stereotypical ways is also apparent in organisations. For example, women in leading positions are not bound to follow a leadership approach based on characteristics typically observed in other women and thus attributed to gender. Women could also take up a less communal and more masculine style or behave like a Queen Bee, i.e. women denying gender discrimination, having a non-supportive attitude towards other women. Moreover, the economy and gender diversity researcher Renee B. Adams reminds us in her article Women on boards: The superheroes of tomorrow? that “gender differences are not always the same as the population gender differences”. Accordingly, studies on women in leadership and board positions may not adequately reflect characteristics in the female population as such.

Apparently, since femininity and feminine are socio-cultural constructs also feminine leadership must be seen as a construct accordingly. As the Danish sociologist Yvonne Due Billing and the Swedish management scholar Mats Alvesson argue in their article Questioning the Notion of Feminine Leadership: A Critical Perspective on the Gender Labelling of Leadership, that “the idea of feminine leadership should be seen as a regulative ideal, a normative construct, rather than an empirical phenomenon”. However, this gives us the opportunity to view feminine leadership as an alternative to the dominant, masculine way of leadership, as it is actually not limited to women only. Thus, it could equally serve as an alternative way of leading for men not identifying with the dominant paradigm of their own gender.

Is There an Ideal Way of Leadership?

Generally, it needs to be stressed that the ideal way of leadership must be defined in relation to context, i.e. whether it needs to be more masculine or feminine. There is no ideal way of leadership in the sense of one best practice. Leaders, whether female or male, need to have a diverse competency profile incorporating both masculine as well as feminine competencies. In this regard, the psychology professor Richard A. Lippa stresses in his article On Deconstructing and Reconstructing Masculinity–Femininity that “extreme femininity in females or extreme masculinity in males is not necessarily desirable”. Hence, in the organisation of the future both men and women need to learn to become more versatile with regard to their respective behavioural style, drawing from a broad set of characteristics and thereby leaving behind gender stereotypes.

There have been already attempts to making leadership styles more mixed or diverse. For example, organisational behaviour scholar Steven Appelbaum and human resource management scholar Barbara Shapiro highlight in their article Why Can′t Men Lead Like Women? the right mixture of qualities, comprising good listening abilities with regard to both hard facts and emotional undertones; being able to lead discussions; mastering the stretch between being authoritarian and democratic, as well as between expressing and controlling emotions amongst others.

The Spanish gender researcher Leire Gartzia and team building scholar Josune Baniandrés underline in their article How Feminine is the Female Advantage? the combination of agentic (masculine) and communal (feminine) qualities. There has been also a clear link established between women’s qualities and transformational leadership, which is perceived as a new way of leadership for a more complex world. Yet, there are concrete approaches especially highlighting female characteristics, such as connective leadership or relational leadership. However, to my knowledge there has not been any attempt to approach gender and leadership from a non-Western perspective, i.e. Chinese philosophy, advocating this approach as an alternative to the currently prevailing ‘masculine’ style or other mixed styles. For a better understanding of a non-Western alternative we will now turn to Chinese philosophy and concepts therein.

Chinese Philosophy, Daoism and Yin-Yang Logic

Next to Confucianism, Daoism is another prominent and influential philosophical school in Chinese philosophy. It came into existence at roughly the same time as Confucianism with its most prominent work, the Dao De Jing 道德经 dating back to 4th century BCE. At its core, Daoism is concerned with harmony between heaven, earth and the human being, which is achieved by following dao 道. Dao is primarily interpreted as the Way, the natural way of things, which inspired the underlying concepts of the Daoist philosophy. Generally, whatever we find in Chinese philosophy is ultimately a reflection of what can be observed in reality, and with specific regard to Daoism: in nature. The three most prevalent concepts in Daoism are dualism, the logic of reversion and the idea of cycles. All these are to be found in nature and represented by the yin-yang 阴阳 symbol. Although yin-yang is an epistemology shared by all philosophies in China, Daoism most heavily draws on that and made yin-yang its core logic.

Yin-yang are alternating, complementary categories and in large present a complex network of classifications, structuring the Chinese perception of reality. They are symbolic and generic, only pointing to a contrast between and in relation of two appearances. Together, they form an integrated and dynamic whole.

Originally, these categories were derived from natural observations, as yin represents the dark (originally recurring to the shady side of a hill), carrying the symbol of the moon and yang means bright (originally recurring to the sunny side of a hill), carrying the symbol of the sun. Accordingly, the two categories establish a cyclical or alternating dualism, as bright/day and dark/night are changing phases. This leads to the logic of reversion or conquest cycle: whatever is yin can turn into yang and vice versa, same as day is turning into night and night into day. The yin-yang pair first appeared in the Yijing, the Book of Changes (one of the earliest books in Chinese history dating back to 9th century BCE), in the context of change. In a major Daoist work, the Dao De Jing (DDJ), however, this logic of alternating contrasts is applied to human beings. It emphasises the mutual complementarity of yin-yang but articulates a clear preference for the female and the feminine. This preference indicates a reversion movement, a ‘return’ from high (strong/masculine) to low (weak/feminine).

This article draws on the yin-yang logic inherent in Daoism to develop a leadership style based on non-Western, alternative values and principles. The DDJ as a starting point is most suitable in this context for two reasons. First, Chinese philosophy by that time was predominantly political philosophy with the objective to convince the ruler of a certain way of government. Accordingly, its ideas and concepts are based in a context of leadership and guiding values. Second, it draws on “traditional feminine images such as the female, mother, valley, and water to symbolize the Dao and advocating humility, yieldingness, and receptivity feminine characteristics attributed to women by the patriarchal culture” as Chinese philosopher scholar Judith Chuan Xu writes in her article Poststructuralist Feminism and the Problem of Femininity in the „Daodejing“. Yet, precisely by drawing on these images and “recommending feminine ways to the male sage as the way to govern the empire, however, the DDJ both implicitly and explicitly breaks down traditional norms and conceptions of Man and Woman”. However, we need to bear in mind that the DDJ is not advocating a feminist perspective; rather, the ideal promulgated therein coincides with what Chinese traditional culture considers being feminine.

A significant change in leadership style seems to be advised especially in light of an expected increased use of artificial intelligence in the workplace, which will create new demands with regard to qualities and personality of the leader, as well as her leadership style. Thus, breaking down traditional norms appears to be vital in developing a viable alternative leadership style utilizable by both women and men, as gender stereotypes and dichotomies are not conducive for either men or women.

Moreover, breaking down traditional gender-based norms is also ethically important, as it focuses on what is truly human, our very essence as human beings, rather than increasing the chasm between men and women. Focusing on our human qualities and what makes as human is especially relevant in the context of rising automation and artificial intelligence, as this is indispensable to differentiate ourselves from machines in the future.

Daoism and Leadership

In this section, I will take up concrete references from the DDJ to explain the feminine, which is for example expressed in values like softness and weakness that are both related to characteristics the DDJ also attributes to water.

The Dao De Jing and the Feminine (Female)

In the DDJ, yin and yang are only used once explicitly in Chapter 42 in the more literal meaning of bright and dark according to Arthur Waley’s work The way and its power: A study of the Tao Te Ching and its place in Chinese thought. Yet, the DDJ makes use of another term indicating the female: pin 牝. This term is used in Chapter 6 (the “valley spirit” as the “mysterious female” from which “Heaven and Earth sprang”) in Chapter 55 (“the union of male and female”) and Chapter 61 (“the female by quiescence conquers the male”). Accordingly, the female “dark” valley spirit plays an important role as from it Heaven and Earth emerge; the female and male belong together as constituting yin and yang respectively, but the female is considered the more powerful.

SOFTNESS AND WEAKNESS

The following three chapters are illustrating the Daoist logic of reversion – also called “conquest cycle” by the American philosophy scholar Michael LaFargue in The Tao of the Tao Te Ching – namely that the soft/female eventually overcomes the hard/male, which is exemplified by quotes from Chapter 36 and 43 respectively: “It is thus that the soft overcomes the hard, And the weak, the strong.”;“What is of all things most yielding, Can overwhelm that which is of all things most hard”, as Waley writes. Also, that the soft and weak is preferred over the hard and supposedly strong is illustrated in Chapter 76: “When he is born, man is soft and weak; in death he becomes stiff and hard. The ten thousand creatures and all plants and trees while they are alive are supple and soft, but when they are dead they become brittle and dry. Truly, what is stiff and hard is a ‚companion of death‘; what is soft and weak is a ‚companion of life‘. Therefore ‚the weapon that is too hard will be broken, the tree that has the hardest wood will be cut down‘. Truly, the hard and mighty are cast down; the soft and weak set on high.”

According to the specific logic inherent in Daoism, softness and weakness represent flexibility, vitality, and therefore are seen as long lasting. This is represented by the female as in yin or pin. On the other hand, the male yang is associated with strength and hardness. Yet, in the context of yin-yang logic as applied in the DDJ, the male yang is construed as the negative, the status to be avoided in the long-term, as hardness is linked with becoming dry, brittle and firm, losing its flexibility and hence vitality and longevity.

THE WATER METAPHOR

Water is mentioned in a number of chapters; thus it presents an indispensable element of Daoist thought and is generally an important element in Chinese history and philosophy.

The values of softness and weakness are so called ‘wateristic’ characteristics. According to Arthur Waley water takes the “low ground”, following the logic of “To be perfect is to invite diminution; to climb is to invite a fall, in line with the yin-yang logic of reversion. Thereby, water serves as a metaphor to illustrate exemplary behaviour throughout the DDJ. Water generally has a “beneficiary role” and has three important qualities according to the Chinese philosophy professor Lin Ma in Lévinas and the Daodejing on the Feminine: Intercultural Reflections. First, it always lies in the lower position but since being soft and flexible it can move to all directions. Hence, it can nourish and embrace everything, as we can read in Waley’s work: “The highest good is like that of water. The goodness of water is that it benefits the ten thousand creatures; yet itself does not scramble, but is content with the places that all men disdain. It is this that makes water so near to the Way.”. Second, since being in the lower position it does not compete. And lastly, because it is associated with soft, flexible, low, weak and powerless it eventually conquers the strong and powerful due to the yin-yang logic of reversion: “Nothing under heaven is softer or more yielding than water; but when it attacks things hard and resistant there is not one of them that can prevail.”. Here, the water metaphor serves to illustrate and underline the actual strength of softness and weakness.

From the water metaphor and the ‘wateristic’ characteristics softness and weakness some more guidance can be derived with regard to exemplary behaviour. From a complete analysis of the DDJ from the perspective of virtue ethics, virtues such as humbleness, modesty, kindness, supportiveness and generosity amongst others can be derived. Furthermore, before-mentioned Michael LaFargue identified a number of themes related to water in his own translation of the DDJ such as a particular excellence consisting in avoiding boasting, excess, desire and competition, while at the same time cultivating a good character by nurturing qualities such as being selfless, calm, unpretentious and intuitive and especially femininity. This feminine way is also linked to keeping a low profile, i.e. not appearing impressive but leading with subtle influence and power.

Developing a Leadership Style Inspired by Daoism

Apparently, the female yin values are more positively connoted in Daoism than the supposedly stronger male yang values. From the sections above a more comprehensive picture of Daoist values as presented in the DDJ emerges.

For the sake of a modern interpretation in a contemporary context, the values derived from the Daoist female characteristics are separated into more strategic values such as flexibility, adaptability and avoiding competition and ethical values such as humbleness (including modesty), selflessness, which is also linked to kindness (including supportiveness), moderation (including avoiding excess and desires), and authenticity through being unpretentious and intuitive over superficially knowledgeable. Originally these all served the purpose of longevity and long-term vitality. Taken together these values nowadays are constitutive for an alternative leadership style, a so-called soft style.

Here, two examples shall be given to illustrate how the two value sets inherent in the soft style approach to leadership could play out in business. Rising implementation of automation and artificial intelligence (AI) will significantly impact the entire organisation in terms of hierarchical structures and the organisation of work as such. In addition, technological change more broadly also impacts the human being and her demands and needs. Thus, transformation of the organisation will not be only driven merely by technological change but also by human beings and her needs and demands affected by technological change, leading to new ideas regarding the organisation of work in the future. Under these conditions, a soft style approach to leadership could be leading the way.

First, if hierarchies are breaking away and the boundaries of roles are becoming more fluent – such as in management expert Peter Drucker’s management outlook and vision of work in the 21st century, adopting a leadership style based on strategic values like flexibility and adaptability, and ethical values like humbleness, kindness and moderation are vital to equally ‘fulfil’ the role of the employee as well as that of the leader. Here, especially the water-like ethical values promote an atmosphere of cooperation as opposed to competition, superiority and thus latent aggressiveness. Moreover, as stressed by organisational psychologist Chomorro-Premuzic, competent people engage in more self-criticism and self-doubt, which is reflected by Daoist humbleness and modesty. Hence, in the context of good leadership he advocates humble leadership as the opposite of charisma, which he links to over-confidence, as in his opinion charisma diverts from actual competence.

In this context it is also important to understand the difference between leadership and management. While leaders are supposed to be visionary, inspiring and motivating, thereby driving creativity, innovation and change, managers on the other hand have more administrative tasks such as taking responsibility for reliable and efficient operations. This understanding of the function(s) of management is linked with a more scientific, Tayloristic approach to business, which in the 21st century seems to be less and less appropriate. Thus, in light of a necessary departure from scientific management, the role of leaders in organisations becomes more important. Leaders are supposed to focus on people and promoting their potential; whereas managers focus on structures and systems. Yet, the ‘soft style’ is breaking with the typical leader-follower relation, as it is based on “leading from behind”, i.e. being supportive but always in the background.

Second, adopting the yin-yang logic can lead to new ways of self-development and self-management altogether. Together with the more strategic water-like characteristics of flexibility and adaptability derived from Daoist softness, it can also improve our resilience for example. By relieving us from thinking in typical Western binary and exclusive categories of either/or it allows us to become more flexible, being able to better tolerate paradox and contradictions, as eventually these are all part of a larger whole. Accordingly, this flexibility also increases our ability to better manage uncertain, contradictory or even chaotic situations. With regard to resilience the yin-yang logic of reversion helps us to avoid hasty judgments of good or bad, as according to this logic, something that looks negative at first glance may ultimately turn into something rather positive. Thus, it can help us to better endure seemingly negative situations.

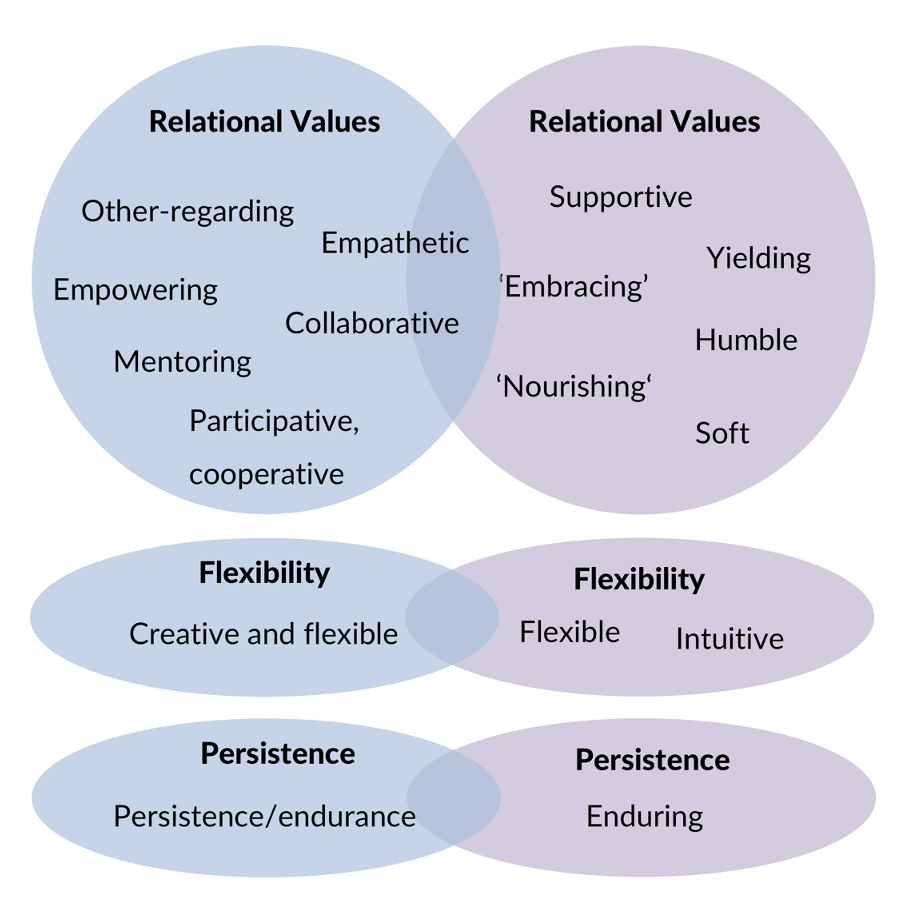

In conclusion, these values and behavioural characteristics derived from the DDJ could promote specific characteristics or attitudes, which enable a supportive, co-operative, non-aggressive leadership style. This style apparently is also very much in line with what other researchers have stated with regard to the female way of leadership as observed empirically.

In light of a high number of disengagement of employees globally (about 70 per cent), which can be also attributed to bad leadership, it is about time to develop and implement a leadership style that is both timely and beyond gender (stereotypes) to sustain the organisation in light of future challenges such as automation and AI.

Figure 1 (developed by the author), Behavioural Characteristics observed in women being in leadership positions (left), and their overlap with Daoist values (right).

Key Take-Aways

This section concludes with five key take-aways from the discussion of more diverse approaches to leadership. First, it has been sufficiently confirmed that emulating masculine behaviour is not necessarily beneficial for women either. Thus, in order to innovate leadership, the organisational culture needs to be revised and less gendered ways of leadership need to be introduced and implemented.

Second, aspects of the Daoist ‘soft style’ approach based on yin-yang are reflected in empirical observations, as well as in Western ‘feminine’ approaches to leadership such as connective leadership or relational leadership. This indicates a strong connection to already present ideas and feasibility regarding the potential implementation of a ‘soft style’ leadership approach due to a shared common basis.

Third, in contrast to other Western approaches that advocate a ‘feminine’ and a “mixed style” approach in leadership, the Daoist approach, however, overcomes the feminine-masculine dichotomy still present in Western conceptions of leadership.

Fourth, the Daoist ‘soft style’ approach transcends gender dichotomy by dissolving the two gender categories through making formerly gendered values available to everyone, i.e. by turning the female physical weakness and softness upside down and promulgating these as values to be adopted by men for successful leadership. Moreover, in Daoism the ‘feminine’ is not construed in relation to the ‘masculine’.

Fifth, this transcendence of gender dichotomy may make this particular leadership style also more accessible to men who do not subscribe to hegemonic masculine values of competition and aggressiveness but rather seek a cooperative style that is rather gender-neutral. In this regard, it is important to bear in mind that gender is actually not only a women’s issue, as in fact it impacts men, women and organisations.

As the organisation of the future will be exposed to significant changes induced through automation and AI; the change in work as such, being more centred on knowledge but also by a generation of employees having different needs and demands, we will need new ways of management and organisation to sustain the organisation in the future. For example, we will need to reduce hierarchical silo-structures, create more agile and flexible ways of organisation and a different set of values in line with these new developments, emphasising our human essence and emotions. In this context, also a different leadership style will be essential for a successful transformation of the organisation.

About Dr. Alicia Hennig

Alicia is holding a full research position as Associate Professor of Business Ethics at the department of philosophy at Southeast University in Nanjing, China. Her research focuses on Chinese philosophy and its application in organisations in the context of values, ethics and innovation. In addition to her research she also has practical working experience gained at Chinese as well as foreign companies in China. Alicia is cooperating with a number of educational and business institutions to promote a better understanding of Chinese culture and thinking, such as ESMT Berlin, the Austrian Center at Fudan University, the Chamber of Industry and Commerce in Frankfurt (IHK Frankfurt), or the German Chamber of Commerce in China (AHK Beijing; AHK Shanghai).

References & Further Reading

Adams, R. B. (2015). Women on boards: The superheroes of tomorrow?. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 371–386.

Alimo-Metcalfe, B. (2010). An investigation of female and male constructs of leadership and empowerment. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25(8), 640–648.

Ames, R. T. (2003). Yin and Yang. In A. S. Cua, (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy (pp. 846–847). New York, US; London, UK: Routledge.

Archer, J., Lloyd, B. B. (2002). Sex and Gender. 2nd Ed.. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Appelbaum, S. H. & Shapiro, B. T. (1993). Why Can′t Men Lead Like Women?. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 14(7), 28–34.

Bell, D. A. (2011). Introduction. In X. Yan (Auth.), A. D. Bell, & S. Zhe (Eds.), E. Ryden (Transl.), Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power (pp. 1–20). Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

Butler, J. (2004). Undoing Gender. New York, US; London, UK: Routledge.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2019). Why do so many incompetent men become leaders? Boston, MA, US: Harvard Business Review Press.

Cheng, C.-Y. (2003). Dao (Tao): The Way. In A. S. Cua (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy (pp. 202–206). New York, US; London, UK: Routledge.

Cheung, C., Chan, A. (2005). Philosophical Foundations of Eminent Hong Kong Chinese CEOs’ Leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 60, 47–62.

Chief Executive Women (2019). Better Together: Increasing Male Engagement in Gender Equality Efforts in Australia.“Bain and Company. Retrieved from https://cew.org.au/topics/ better-together/. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Dempster, L. (2016). If you doubted there was gender bias in literature, this study proves you wrong. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/jun/10/if-you-doubted-there-was-gender-bias-in-literature-this-study-proves-you-wrong. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Diehl, A. B. & Dzubinski, L. M. (2016). Making the Invisible Visible: A Cross-Sector Analysis of Gender-Based Leadership Barriers. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 27(2), 181–206.

Donato-Brown, D. (2019). The sexism in surgery is shocking 1 from ‚banter‘ to discrimination. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/08/sexism-surgery-shocking-colleagues-patients-diversity. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Drucker, P. F. & Wartzmann, R. (Eds.) (2010). The Drucker Lectures: Essential Lessons on Management, Society and Economy. New York, US: McGraw-Hill.

Due Billing, Y. & Alvesson, M. (2000). Questioning the Notion of Feminine Leadership: A Critical Perspective on the Gender Labelling of Leadership. Gender, Work and Organization, 7(3), 144–157.

Eagly, A. & Carli, L. L. (2003). The female leadership advantage: An evaluation of the evidence. The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 807–834.

Eagly, A. (2007). Female leadership advantage and disadvantage: resolving the contradictions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 1–12.

Eagly, A. H., Beall, A. E., & Sternberg, R. J. (2004). Introduction. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Psychology of Gender (pp. 1–8), 2nd Ed.. London, UK: The Guilford Press.

Enderstein, A.-M. (2018). (Not) just a girl: Reworking femininity through women’s leadership in Europe. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(3), 325–340.

Esser, A., Kahrens, M., Mouzughi, Y., & Eomois, E. (2018). A female leadership competency framework from the perspective of male leaders. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 33(2), 138–166.

Fang, T. (2011). Yin Yang: A New Perspective on Culture. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 25–50.

Faniko, K., Ellemers, N., Derks, B., & Lorenzi-Cioldi, F. (2017). Nothing Changes, Really: Why Women Who Break Through the Glass Ceiling End Up Reinforcing It. Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, 43(5), 638–65.

Gartzia, L., Baniandrés, J. (2019). How Feminine is the Female Advantage? Incremental validity of gender traits T over leader sex on employees‘ responses. Journal of Business Research, 9, 125–139.

Giesa, C. & Schiller Clausen, L. (2014). New Business Order: Wie Start-ups Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft verändern. Muenchen, Germany: Carl Hanser Verlag.

Gipson, A. N., Pfaff, D. L., Mendelsohn, D. B., Catenacci, L.T., & Burke, W. W. (2017). Women and Leadership: Selection, Development, Leadership Style, and Performance. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(1), 32–65.

Glass, C. & Cook, A. (2016). Leading at the top: Understanding women’s challenges above the glass ceiling. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 51–63.

Goodman, J. S., Fields, T. L., & Bloom, T. C. (2003). Cracks in the Glass Ceiling: In what kinds of organizations do women make it to the top?. Group & Organization Management, 28(4), 475–501.

Granet, M. (Auth), Porkert, M. (Transl.) (1985). Das Chinesische Denken. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Hansen, C. (2007). Daoism. Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/daoism/. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Hennig, A. (2017). Applying Laozi’s Dao De Jing in Business. Philosophy of Management, 16, 19–33.

Hicks, M. (2018). Why tech’s gender problem is nothing new. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/oct/11/tech-gender-problem-amazon-facebook-bias-women. Accessed 1 July 2020.

Hunt, V., Prince, S., Dixon-Fyle, S., Yee, L. (2018). „Delivering through diversity.“ McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/ business%20functions/ organization/our%20insights/delivering%20through%20diversity/delivering-through-diversity_full-report.ashx. Accessed 15 June 2019.

Jullien, F. (2004). A Treatise on Efficacy: Between Western and Chinese Thinking. Honolulu,

HI: University of Hawai’i Press.

Kohn, L. (2009). Introducing Daoism. London, UK: Routledge.

Kolb, D. M., Fletcher, J. K., Meyerson, D. E., Merrill-Sands, D., & Ely, R. J. (2003). Making change: A framework for promoting gender equity in organizations. In R. J. Ely, E. G. Foldy, M. A. Scully (Eds.), Reader in gender, work, and organization (pp. 10–15). Malden, MA, US: Blackwell.

LaFargue, M. (1992). The Tao of the Tao Te Ching. New York, US: State University of New York (SUNY) Press.

Lee, Y.-T., Han, A.-G., Byron, T. K., & Fan H.-X. (2008). Daoist leadership: theory and application. In C.-C. Chen, & Y. T. Lee, (Eds.) Leadership and Management in

China: Philosophies, Theories and Practices (pp. 8–107). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Li, P. P. (2014). Toward the geocentric framework of intuition: the Yin-Yang balancing

between the eastern and Western perspectives on intuition. In M. Sinclair Ed.) Handbook of Research Methods on Intuition (pp. 28–41). Cheltenham, UK: Edgar Elgar.

Lipman-Blumen, J. (1992). Connective Leadership: Female Leadership Styles in the 21st-Century Workplace. Sociological Perspectives, 35(1), 183–203.

Lippa, R.A. (2001). On Deconstructing and Reconstructing Masculinity–Femininity. Journal of Research in Personality, 35, 168–207.

Lorenzo, R., Voigt, N., Tsusaka, M., Krentz, M., & Abouzahr, K. (2018). How diverse leadership teams boost innovation. Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved from https://www.bcg.com/de-de/publications/2018/how-diverse-leadership-teams-boost-innovation.aspx. Accessed 15 June 2019.

Ma, L. (2009). Character of the Feminine in Lévinas and the Daodejing «道德经». Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 36(2), 261–276.

Ma, L. (2012). Lévinas and the Daodejing on the Feminine: Intercultural Reflections. Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 39 (supplement), 152–170.

McKinsey & Company (2017). Women Matter: Time to accelerate. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/gender-equality/women-matter-ten-years-of-insights-on-gender-diversity/de-de. Accessed 15 June 2019.

McKinsey & Company (2018b). Women in the Workplace. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/gender-equality/women-in-the-workplace-2018. Accessed 15 June 2019.

Miller, J. (2006). Daoism and Nature. In R. Gottlieb (Ed.), Handbook of Religion and Ecology (pp. 220–235). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Moeller, H. G. (2004). Daoism Explained: From the Dream of the Butterfly to the Fishnet Allegory. Chicago, US: Open Court Publishing.

Moore, C. A. (1967). Introduction: the humanistic Chinese mind. In C. A. Moore (Ed.), The Chinese mind: essentials of Chinese philosophy and culture (pp. 1-10). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii.

Niedenführ M. & Hennig A. (2020). Confucianism and Ethics in Management. In C. Neesham C. & S. Segal (Eds), Handbook of Philosophy of Management (pp. 1–13). Netherlands: Springer.

Paechter, C. (2006). Masculine femininities/feminine masculinities: power, identities and gender. Gender and Education, 18(3), 253–263.

Peng, M. W., Li, Y., & Tian, L. (2015). Tian-ren-he-yi strategy: An Eastern perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33, 695–722.

Pickett, M. (2019). „I Want What My Male Colleague Has, and That Will Cost a Few Million Dollars’. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/18/magazine/ salk-institute-discrimination-science.html. Accessed 15 June 2019.

Post, C. (2015). When is female leadership an advantage? Coordination requirements, team cohesion, and team interaction norms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, 1153–1175.

Powell , G. N., & Butterfield, A. D. (2015). The glass ceiling: what have we learned 20 years on? Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2(4), 306–326.

Rosener, J. (2011). Ways Women Lead.“ In P. H. Werhane, M. Painter-Moorland (Eds.), Leadership, Gender and Organization (pp. 19–29). Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York: Springer.

Rutt, R. (2002). The Book of Changes (Zhouyi). New York, US; London, UK: Routledge.

Sanders, M., Hrdlicka, J., Hellicar, M., Cottrell, D., & Knox, J. (2011). What stops women from reaching the top? Confronting the tough issues. Bain and Company. Retrieved from https://www.bain.com/insights/what-stops-women-from-reaching-the-top/. Accessed 15 June 2019.

Sanders, M., Zeng, J., Hellicar, M., & Fagg, K. (2015). The Power of Flexibility: A Key Enabler to boost Gender Parity and Employee Engagement. Bain and Company. Retrieved from https://www.bain.com/insights/the-power-of-flexibility/. Accessed 15 June 2019.

Uhl-Bien, M. (2011). Relational Leadership and Gender: From Hierarchy to Relationality. In P. H. Werhane, M. Painter-Moorland (Eds.), Leadership, Gender and Organization (pp. 65–74). Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York: Springer.

Waley, Arthur (Ed.) (1958). The way and its power: A study of the Tao Te Ching and its place in Chinese thought. New York, US: Grove Press, Inc.

Walker, R. C. & Aritz, J. (2015). Women Doing Leadership: Leadership Styles and Organizational Culture. International Journal of Business Communication, 52(4), 452–478.

Weyer, B. (2007). Twenty years later: explaining the persistence of the glass ceiling for women leaders. Women in Management Review, 22(6), 482–496.

Wong, D. (2014). Comparative Philosophy: Chinese and Western. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/ archives/spr2017/entries/comparphil-chiwes/. Accessed 19 February 2018.

Xu, J. C. (2003). Poststructuralist Feminism and the Problem of Femininity in the „Daodejing“. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 19(1), 47–64.

Yang, C. F. (2006). The Chinese conception of the Self: Towards a person-making perspective. In U. Kim, K. S. Yang, & K. K. Hwang (Eds.), Indigenous and cultural psychology: Understanding people in context (pp. 327–356). New York, US: Springer.

Über die Autoren

Dr. Alicia Hennig ist Philosophin, China Expertin und international Associate Professor. Ihre Themen: Wirtschaftsethik, Daoistische Konzepte für Leadership und Management.

Lena Schiller ist Co-Director, Politikwissenschaftlerin, Buchautorin, Coach und Ausdauersportlerin.

Ihre Themen: New Work, Female Leadership und Digitale Transformation.